Anna and Magnus built a life together. They had a home with three kids and a dog. Then they separated. This is where The Love That Remains begins, but as time passes and the reality of their divorce sets in, they’re left to move through a future strained by their unraveling.

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason’s latest film echoes the radiant visual language of his previous, the 19th-century period piece Godland and contemporary drama A White, White Day. And though its subject matter is heavy, the tone here is admittedly lighter. The aforementioned dog, Panda, even took home the Palm Dog Award at Cannes this year, which — and I’m being very serious here — is an actual award given out. On the surface, The Love That Remains is a story about normal people with normal feelings and normal problems, like how to raise a family while going through a divorce and what to do when one of your kids — who are played by Pálmason’s children — shoots the other in the chest with a bow and arrow. (He’s fine, but he’s gonna need a new sweater.)

Buried deep are existential questions. “Often I think about what is the meaning of all this? When you go through life, you have moments of doubt about just life and things and what’s the meaning of all of it,” Pálmason tells me. “It’s so silly, all of it.” He’s right. It is silly. It’s also life? As we pass through the seasons with Anna and Magnus, we begin to learn what’s left between them.

The director sat down with The Verge to talk about what it’s like to direct your own kids and how he balanced shooting Godland and The Love That Remains at the same time.

Interview edited and condensed.

The Verge: I want to start here. Godland had such a weighty story. The Love That Remains feels lighter, but I think they share similar themes. Do they feel similar to you? Different? I’d be curious to hear you talk about that relationship.

Hlynur Pálmason: Because Godland was this period film and there’s almost like a heaviness with each period film because you have to create everything. You just can’t just take a camera and start shooting whatever. So there was this feeling of wanting to do something with a little bit different energy, like more playful and something that we could almost just go out and shoot. And also, just with a smaller budget and smaller crew. I mean, it was actually very small in Godland, but even smaller in The Love That Remains.

But there is this thing that I have after I moved back home to Iceland, I was always trying to figure out a way of stretching time so I could have more time with each project, which is difficult because of finances. But we kind of found a way to do it by working in parallel on a couple of projects. But we’re developing and writing and shooting various things. And then when we feel like it kind of has formed and we feel that it’s ready and the energy is ready, we kind of select the project that we move forward with. The Love That Remains, in many ways, has been going on for such a long time. Even the first image we shot was in 2017.

It’s quite a long process. Sometimes when you talk about other projects, they are almost happening parallel. I remember shooting scenes from Godland and the same week, shooting a scene for The Love That Remains, which is crazy to think about.

You keep all these different threads in your head?

Yeah, I think it all kind of… I don’t know. I feel like, I think some people would find it negative if things are talking too much together or eating into each other, like projects. But I kind of like when it happens because it kind of shakes you and makes you even doubt things or pushes the project. If something is turning out really interesting in one project, it kind of feeds into the other one or it kind of pushes the other one to do better.

I would never be able to make one film at a time, because financially it wouldn’t work at all. And I would only make three films during my lifetime and I would have to have other works, teacher and other things.

The title, The Love That Remains, is really more of a question: what love remains? Was making this film a way for you to answer that?

Often I think about what is the meaning of all this? When you go through life, you have moments of doubt about just life and things and what’s the meaning of all of it. If I’m in a relationship for many years and then we get separated and my fiancée would just find another, what is it? It’s so silly, all of it.

But there’s also a brighter side: how precious time is and how you spend it and actually, who you spend it with and who you decide to spend it with. Because time is probably precious because it moves so fast. You kind of have to, try to capture what you can get or moments with ones you love. And yeah, I’ve been thinking a lot about time and you can see that both in Godland and in The Love That Remains, where really, there’s an emphasis on time, on how it moves.

The opening sequence is really lovely. You establish this family by holding a portrait of them at the table. It almost feels like a sitcom, but then the music isn’t sitcom music at all?

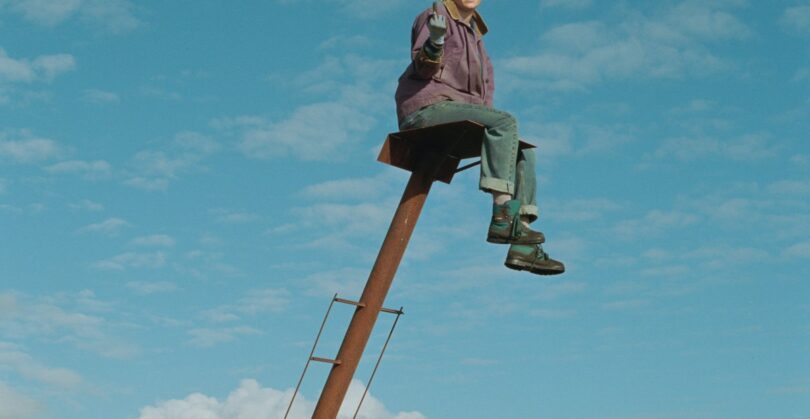

Yeah, I did think a lot about after I filmed this image, this image of the roof getting ripped off of the old studio, that was the first image I filmed for the film.

Yeah. And when I had that image, I knew exactly what would happen afterward. And that’s often the case when I’m working. I often don’t know what happens unless I record a sound or I film an image, and then I kind of just react to the image and then I know what happens. It’s kind of like you get stimulated by something you experience or film, and then you write the next scene or you know what’s going to happen. And I think just when I saw this image of the roof, not while I was filming it, because I was not in a good state then, but afterwards, I knew exactly how the film should start.

We should be introduced to each family member and it should be this warm feeling before things begin to fall apart. But also, afterward you begin to find out that it’s actually a fractured family, they’re not together anymore. And often the case is when I’m making something, I know what I don’t want the film to be, but I don’t always know what I want it to be.

It’s fun and playful, but sweet and sincere, too.

But when does it become sentimental? And that’s something that I don’t like. I only like it in a David Lynch film or something. I love it in his films, but I could never do that. So I tried to balance it in a different way, but it is a fine line.

It’s your own children in this film too, right? What’s it like to direct your kids?

It’s fun. But I think it’s okay because I have so many, because basically they’ve been in all my projects except for my debut and also my short films. And so it’s very natural for me to just keep collaborating with them and spending time with them. It’s not something I force them to do. I mean, I do pay them for their work, but I think they also just really like being part of our family or the filmmaker family because it’s a very, very close group of friends and we’ve been working on all of the projects together.

The idea of being a director and having to make many decisions and at the same time, having your kids in the space, I’m sure it adds some fun nuance.

Yeah. I mean, sometimes it’s total chaos, but I think number one is that we have enough time, that we’re not pressed on time. There’s no AD [assistant director] that is saying, “Okay, we have to move.” It’s never happened in my life. We just film until we have something that we like and then we move on. What I like about our sets is that they’re very calm and effortless. There’s no catering, there’s no hierarchy, there’s no chairs, there’s no screens. It’s very, very basic.

The Love That Remains is in select theaters now.

Source link